This post has been a while in the making! I’ve been wanting to write a terminology post about chintz for a while, but I wanted to do it right and include a bit of the history, how it was used and how it was made. That made it a bit longer than I’d originally envisioned, so be ready for a rather extensive overview! (If you don’t like those, feel free to just look at the pictures, chintz is very pretty!)

Chintz is a name referring to cotton fabric or paper with flower patterns. In this post, I’ll give some information on the historical fabric. It’s one of my favorite patterns, it’s often used in historical (mainly 18th century) dress and in Dutch folk costume. I’ll try go give a brief overview of the history of chintz, it’s characteristics, patterns and how it’s used in fashion. My focus will be on chintz in the Netherlands and traded by the East-Indian Trading company, but I’ll also try to give some more global information.

A short definition

Lets start with a brief section on the term ‘Chintz’ I’m using. In Dutch, we call this fabric ‘Sits’, and use it to refer to the glazed cotton painted and/or printed with flowered patterns, originally coming from India. This post is about what the Dutch would call ‘sits’. The translation in English is the term ‘chintz’. In time the English term chintz has evolved and become the name of many different types of flower patterns as well as the original patterns. It’s also sometimes used for basic plain cotton. I’ll focus on the Dutch meaning for ‘sits’ or chintz in this post. Most of those chintzes are 17th or 18th century, maybe early 19th century. All later chintz fabrics are based on these historical patterns. They were originally Indian, but when chintz gained popularity, similar style printed cotton was also produced in Europe. I’ll start off with some images, to clarify what I’m talking about.

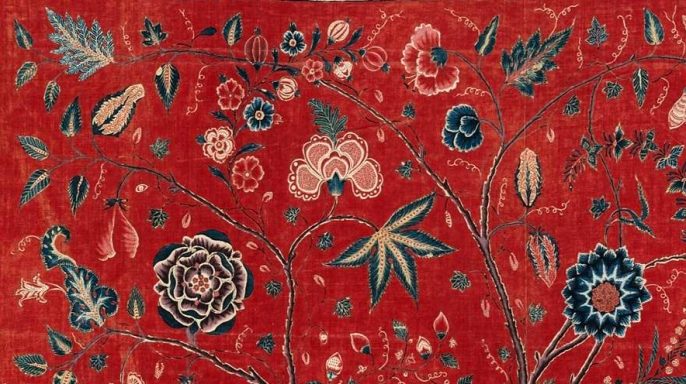

This is Indian chintz:

Part of a kids blanket, quilted, ca. 1725 – ca. 1750. Made in India. Collection Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

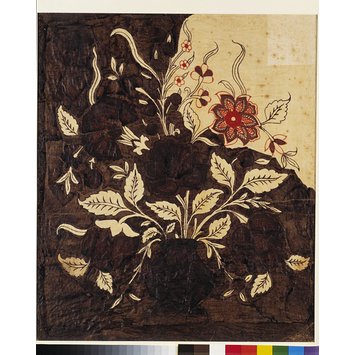

Stylized flower patterns. The most typical version is of blue and red flowers on a pale background. There are different colors as well though. This is also Indian chintz:

Detail of Palempore of chintz with tree pattern , ca. 1725 – ca. 1750, India. Collection Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

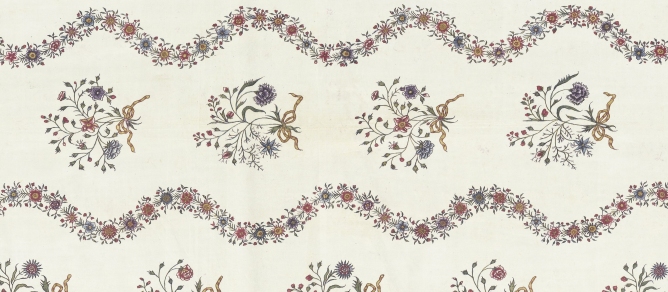

These two examples are typical for the type of floral patterns. The chintz below is much more ‘European looking’, but still also made in India (you can clearly see it’s for the European market though). As you can see, it has a much later date, indicating how the chintz became more ‘European’ and evolved with fashion.

The following image is of a pattern also often named chintz (in English, it wouldn’t be ‘sits’ in Dutch), but which is much more modern than Indian chintzes. To my eye, it’s also much more English, and there’s generally a lot more roses and pink in these more modern fabrics. This is not what this post’ll be about. A good indication if a chintz is Indian or Indian-inspired is to look at colors. Original chintz was mostly white, blue and red. The reason for this is that the white cotton was dyed with natural dyes, which were mostly red and blue, with some yellow. All other colors were a mix of those. Greens and purples you see, although they are rarer. Orange and pink are almost nonexistant. Another cue is the flower style, original chintz flowers were very stylized and almost ‘flat’. They became a little less stylized as time went on, but nothing as life-like as the image below.

Modern ‘Chintz’. This is not what I’ll be talking about.

The rise & fall in western Europe

Chintz was brought to the Netherlands by the VOC, the East-Indian Trading company. They started around 1600, but chintz didn’t really start to play a role in Europe until about 1675. It initially gained popularity as an interior fabric, later also as dress fabric. Chintz was imported most notably from Bengalen, Ceylon, Coromandel and Suratte, the latter two being the most important. Some chintz was probably also traded into the Netherlands via England. Indian chintz was copied from the very start, but especially in the beginning these copies weren’t very good. The Indians had a way of binding the color to the cotton to make the fabrics keep their color after washing, and they hand-painted the fabrics. Early European copies didn’t keep their color well, and were block-printed instead of painted. Nevertheless, many companies started making imitations of chintz, and started trying to copy the process to keep the colors, getting more successful as they went.

‘Onderst oerlof’ (under jacket) from Hindeloopen. The main body is of European cotton print, the front and sleeves (which would be visible), of the higher quality Indian chintz.

The copying happened in different European countries, but not all of them were happy with this popularity. In 1681, France banned both importing cotton and printing it to protect their silk industry. England followed in 1700 with a ban on importing chintz, and in 1721 a ban on printing cotton, again to protect it’s own linen, wool & silk industries. The English did keep trading in chintz, however, and still made printed cotton for export. Given the bans in England and France, it’s not surprising that cotton printing flourished in the Netherlands from that time.

This started changing around 1750, when the economy in the Netherlands started to fail. The bans in France were lifted in 1759, giving rise to a flourishing cotton print industry. One of the most well-known chintz factories, Oberkampf, was located near Versailles in Jouy-en-Josas. This town still gives it’s name to the famous toile-de-jouy fabrics.

Cotton printed fabric. This sample was made by Oberkampf around 1800. These type of fabrics are still known as toile-de-jouy, after it’s original place of creation. V&A. (We wouldn’t call this chintz though, because it lacks the stylized flower patterns)

Printed cotton fabric by Oberkampf, 1770–75, MET museum

England held on to the bans a little longer, lifting them in 1774, finally allowing printing pure cotton fabrics. New printing techniques meant they also caught up to the Netherlands quite quickly, where innovation stayed behind.

English made printed cotton, early 19th century. V&A

The chintz trading and factories disappear almost entirely in the Netherlands between 1785 and 1815. Archives show 80 chintz-shops in Amsterdam in 1742, 117 shops in 1767, but sharply falling numbers between 1771 and 1776, even more companies fail in the 1780’s. The VOC officially ceased to exist in 1800, after almost a century of decline and growing debt. Changing fashions eventually meant the end of the chintz fabrics. Even though printed cotton was there to stay, the Indian(inspired) flower fabrics went away. Several regional Dutch costumes held on to chintz a lot longer though, some surviving until today.

Interiors

A lot of chintz was not used for clothing, but for home decorations. Curtains, wall hangings and chair coverings are all seen, but bedspreads and blankets seem most popular of all. It seems that using chintz in your interior caught on a little earlier than in clothing.

Dollhouse of Petronella Dunois, ca. 1676. Rijksmuseum. The red room has chintz walls

Clothing

Chintz was also often used in clothing. All existing chintz clothing is from the 18th century, when it reached it’s peak in popularity. It was already worn in the 17th century though, as shown by the girl portrait below. This is one of the earliest depictions of chintz being worn.

Emanuel de Witte, 1678

Despite it’s popularity, chintz never really was used much by the upper class for their best clothes. These fashions were very much influenced by the French court (even in the Netherlands), and employed very rich fabrics. Silks most commonly, often embroidered with silver & gold thread. Nevertheless, chintz was worn by the upper classes. Initially, you mostly see it used in ‘undress’. These were clothes worn at home, for non-official occasions or items such as dressing gowns. So it were the type of clothes not many see, but also the ones for less official occasions. This probably also explains why you don’t see many portraits of high-class women wearing chintz, they owned it (records of property show this quite clearly), but didn’t wear it for such a formal thing as having your portrait painted.

What we in Dutch call a ‘Japonese gown’. A dressing gown for a man, strongly influenced by Japanese kimonos. At this point in time (early 18th century), the Dutch were the only ones allowed to trade with Japan. Fries museum

A rare example of a chintz Francaise, many more skirts and jackets exist than gowns, Francaises are even rarer. This was probably an (upper) middle class gown. An upper class woman would’ve been more likely to use silk. Rijksmuseum, ca 1780

As chintz gained popularity in the highest classes, the higher middle class followed, as did the lower middle class. The lowest classes didn’t own much chintz. For the middle class, chintz would’ve been much more valuable and you therefore do see it on prints/paintings of middle class women. There wasn’t much difference between city and country wear in this.

Girl from Sneek (city in Friesland) in her wedding clothes. Tragically, she died in childbirth age 16.

Although we see a lot of chintz dressing gowns for men in the higher circles, it seems that for daily wear chintz was by far most commonly worn by women. Baby clothes are very common at the moment in museums, probably also because little fabric was needed, so jackets and skirts could easily be re-made into baby clothes when necessary. Because you could wash chintz well without it fading, it was very suitable.

Baby Jacket, probably re-made from a skirt.

By far more jackets exist nowadays than full gowns. Skirts of chintz have also survived a lot. You do see a bit more skirts, dresses and capes with the richer classes than with the middle class, where jackets are more common (Again, we know this from inventory lists). Probably because jackets require less fabric. You also often see border patterns on skirts, indicating that fabric was specifically made for skirts.

Chintz skirt

Aside from gowns, jackets & skirts, you also see chintz in powder capes, or as lining of sun hats.

Short chintz cape. ModeMuseum Provincie Antwerpen

The lining of a sun hat, the top would be straw. This particular shape was worn over a huge lace cap in the province of Friesland.

Records show that chintz was worn throughout the Netherlands, but you do see it most often in the Northwest, around the coast. This makes sense, as they are either closer to Amsterdam (the founding city of the VOC), or have their own trading ports. This is also why a lot of existent chintz is in museums in these regions.

Chintz jacket & skirt in the Fries Museum, in the north of the country

Regional costume

When chintz started to go out of fashion, it was also in these regions in the north-west that it was kept most. During the 18th century, we know that specific regional clothing was worn in certain areas. This could be either only be a specific form of headdress, or influence more items. Chintz survived in several regional costumes much longer than it did in regular fashion. Most well known is the Frisian town of Hindeloopen, which had grown wealthy from trade. The Hindeloopen costume was worn daily by women until the 2nd half of the 19th century, but has been kept alive by an active community. The society of Aald Hielpen still wear their costume for special occasions and events. The most well-known item of the Hindeloopen costume is the Wentke, a long coat of chintz worn by the women.

Hindelooper bridal costume.

Back of a Wentke. Red patterns were most common, blue was worn for mourning.

Indian chintz survives up to today in the costume of Bunschoten-Spakenburg, which is still worn daily by a group of women. They wear an item called a ‘kraplap’ over the shoulders, made of heavily starched cotton. It can be made in all types of patterns, but the most valued are the ones from original Indian chintz. Because the kraplap has grown in size over the centuries, the original kraplappen don’t have enough fabric. If you’re lucky enough to find 2 of the same fabric, they are very carefully pieced together. These are the most valuable of kraplapen, and very coveted.

Process

Chintz is a cotton fabric, with the colors being applied after weaving (as opposed to brocade for instance, where the pattern is woven in with the cloth). How exactly the colors were applied depends on location and time. Below a rough overview, as I’m not a chemist, nor an expert on dying. Be aware that the exact substances used could differ.

Original Indian chintz was mostly hand painted, sometimes block printed with smaller wooden blocks. This chintz had a very specific process to apply the different colors. Base colors were blue, red and yellow. Green and purple exist in chintzes as well, but would always be made by applying blue/yellow and blue/red on top of each other. The very special thing about Indian chintz was that it held its colors really well. This was due to the dying process used, some which weren’t discovered yet in Europe when chintz was first imported.

The first step (after bleaching and preparing the cotton) were the black outlines. These were painted directly on the fabric. After the black, the red would be applied. The red dye wouldn’t actually be applied to the fabric though. Instead, everything which would have to turn red was treated with mordant, a chemical substance which would later bind the color to the fabric. If there would be a ‘white’ area within the red, this would first be treated with wax before the mordant was applied. After applying the mordant (once or twice for lighter or brighter red), the cloth is dried and washed and rinsed. The mordant has now set, and only then the whole cloth is put into a dye bath, where only the parts treated with mordant will change color. After dying, the whole cloth can be bleached a bit again, because the white might’ve changed a bit to yellow. The next step would be to apply the blue, painting with indigo. For indigo, everything which does not need to be blue would be covered in wax. The wax-covered cloth would then in its entirety be put into the indigo dye. After dying, the cloth would be boiled to remove the wax again. After the blue, some fabrics would be treated with red again for brighter colors. Lastly, the yellow would be painted on, on top of the blue where you’d want green. This yellow tends to be a bit less well washable than the blue and red though.

In Europe, most chintzes were printed instead of hand painted, with large printing blocks. To be able to use the mordants with blocks, it had to be thickened as opposed to the very thin mordant used for painting. Another difference was that in Europe, some techniques existed enabling the printers to directly dye blue with the indigo, without having to use the wax method. For yellow, Europeans mostly used a mordant again, as opposed to the direct dye used in India.

These fabrics below were made when an interest in chintz began to rise again in the early 20th century and show the process. Collection of the V&A

As a final step, most chintz was glazed by applying pressure to the cloth. Many of the reproductions I’ve seen of chintz miss this glaze, but it is very apparent on most originals! That shine to the fabric is also one of the things which gives it it’s luxurious appearance.

More pictures: If you want to see more examples of chintz clothing, like the red chintz gown below, I’ve got a pinterest board on chintz here.

EDIT: Since writing this terminology post, I’ve written a couple more posts about chintz. The first two were both inspired by the 2017 exhibition in the Fries museum, and feature many pictures of items in their collection. This one is about colors and patterns in chintz, and this one about how it was worn. And this final one is about the 2019 exhibition on chintz in the Rijksmuseum.

Sources

My main source for all of the above information is the book ‘Sits, oost-west relaties in Textiel’ (‘Chintz, east-west relations in textile’, see reference below). This is also my only source, which is not very good practice when it comes to research. I’ve found it to be the only Dutch book about chintz to exist at the moment of writing this blog post. In English literature there’re a couple more books, but not many. (I’m making a wish-list!) I personally suspected more to be available when I went looking, especially because chintz is still quite well known in the Netherlands due to it’s importance in regional costume. All books on regional costume seem to refer to this one source. Having said this, the book was written by scholars, and is based for the most part on primary sources. This means that the information comes from inventories of the V.O.C., from inventories of 17th and 18th century shops and homes, from letters and from 18th century books (for instance on fabric-printing). The list of sources used in the book is extensive, and each chapter was researched and written by another author. Given all of this, I trust this source enough to use it as my only reference. As it’s never been re-printed and only available second-hand, nor has been translated to English, I felt free to share the information and images. Good news though; a new publication has recently come out! With a new exhibition on chintz, a new book has been written. I’ll definitely write a post once I’ve visited the exhibit.

The book:

Sits, Oost-West relaties in Textiel

By the Rijksdienst Beeldende Kunst (National service Visual arts) , the Hague, together with the Rijksmuseum voor Volkskunde (State museum of Anthropology), Nationaal Openlucht Museum Arnhem (Open air museum), Groninger Museum, and the Gemeentemuseum the Hague.

On the occasion of the exhibition ‘Sits, Oost-west Relaties in Textiel’.

Published in 1987, no reprints

EDIT: At time of writing this original post, only the book mentioned above was available. However, I’ve since collected a number of new publications on chintz. These all come highly recommended.

- Sits, Katoen in Bloei – Gieneke Arnolli (in Dutch)

- Pronck & Prael, Sits in Nederland – Winnifred de Vos (in Dutch)

- The Cloth that Changed the World – Sarah Fee (in English)

Amazing article ! Thank you Myrth !

You’re welcome!

Interesting! Great article. I’ve always called glazed cotton chintz, regardless of pattern (or not). I always thought of the sheen as the defining quality. But of course most is flowery. And those jacket and coat backs really did the most of the pattern. Thank you!

Thank you! I think the English word is used in a lot of ways aside from this one, and probably also for plain glazed cotton. It’s funny how when some things disappear from fashion, other objects take over their names and meaning. (I think something similar happened with muslin, which was very thin fine cotton during the Regency, but then got used for mock-up fabric, and somehow now we also call mock-ups themselves muslins 😉 ). The Dutch term always stayed very specifically related to the Indian fabric, but probably also because that fabric actually stuck around in regional costume, and didn’t go away completely. So in a way this is more a terminology of ‘Sits’ than ‘chintz’, but that would’ve made everything a bit confusing for English readers ;).

And then to top it off, I’m Norwegian. 😆 Maybe chintz is flowery fabric on the Isles?

Thanks for this detailed overview, and all the lovely pictures! I’d love to make something from chintz at some point- it’s so gorgeous! I hadn’t thought of lining a straw hat with it before, but that would be really cute. Do you have any idea if that was a specific regional practice, or was it just the shape of that hat? I know that lining hats with silk was a more widespread practice.

You’re welcome! The shape of these hats is definitely very specific for Friesland, they were worn over a huge lace cap the same size (Not kidding, will post some images of those in the future, they had on at the chintz exhibition I just visited). But general round bergere sun hats were worn more widely, and I did find a couple in chintz. (http://emuseum.history.org/view/objects/asitem/classification@12/47/title-desc?t:state:flow=d805bc4d-4cf5-42c2-aba0-6bfc1eaeab5e) Provenance is Dutch again though mostly… But I do suspect it might’ve happened in the US (areas with a lot of Dutch immigrants?) or in France. Especially in the Provence they also wore quite a bit of chintz. Couldn’t find any examples quickly though.

Pingback: Chintz in the Fries museum – color & pattern | Atelier Nostalgia

Pingback: Chintz in the Fries museum – How chintz was worn | Atelier Nostalgia

Pingback: Chintz in the Rijksmuseum | Atelier Nostalgia

Pingback: CoCoVid – All about Chintz! | Atelier Nostalgia

Reblogged this on The Amazing Mirvana and commented:

I am loving this fabric.